WHY TEACH MUSIC: THE IMPERATIVE OF MUSIC EDUCATION IN MONTESSORI CLASSROOMS

By Michael Johnson

A great deal of people have the mathematical formula i + c = n emblazoned in their brain, where i = a musical instrument, c = children, and n = noise. As Mario Montessori wrote in his 1956 article about his mother’s music program, many adults believe children “should be seen and not heard” (Montessori 1956). Perhaps this explains why so many teachers avoid making music in their classrooms. For the children to work on music, they must make sound, and where else but in a Montessori classroom should the environment be sound-free, so the children can concentrate as they occupy themselves with their various activities?

Many teachers even balk at playing music in the background during in the work period, for fear the children won't be able to concentrate. Their fears are not unfounded. A study conducted by Mark Lemouse for HealthGuidance.org, found that people of all ages were more productive in an atmosphere of silence than in an atmosphere in which music was playing (Lemouse 2015). Perhaps because of this, music gets a bad rap in traditional classrooms; it requires making sound, and sound distracts.

But, to put it lightly, silence seldom prevails in Montessori classrooms. According to Phyllis Pottish-Lewis, “A perfectly functioning classroom should be noisy” (Pottish-Lewis 2014). In the Primary, the atmosphere buzzes with children moving, speaking, and going about their individual work. In the Elementary, the children’s conversations, their debates, and their collaborations often generate background noise.

Plus, studies about the perils of having music playing in the background while children work contradict each other. One study conducted in 2010 corroborated Lemouse’s findings. Researchers gave three groups of college students a reading comprehension test while music played in the background: one group listened to Hip Hop, another group listened to Classical, and the third group listened to no music. The study concluded that “the participants who scored the highest in the reading comprehension task were the control group who performed the reading task in silence” (Choi 2010).

Another study published online in Educational Studies, however, found that when calming music played in the background during children’s work it “led to better performance…when compared with a no-music condition” (Hallam, Price, Katsarou 2010).

With everyone contradicting each other about whether music affects or ruins children’s concentration, should you or shouldn’t you have music in your classroom?

The short answer; you must.

When you share music with your children, you create community, you develop in them all of the same skills as other academic pursuits like Math and Language, you provide opportunity for refining Grace & Courtesy, you help your children with emotional control and body regulation, and, most importantly, you have fun.

MUSIC IS COMMUNITY

Merriam Webster defines community as “a group of [people] leading a common life according to a rule.” This is precisely what the children do when performing an authentic folk song or singing game together. For the length of a performance the children non-verbally agree to live by not just one, but a plethora of unspoken “rules” that govern their behavior to the benefit of everyone.

Some of the “rules”, such as “Use your best singing voice”, or “Keep your hands to yourself” come from the teacher as necessary to maintain discipline. But many of the “rules”, such as what movements to perform at what time, or when to lead and when to follow, arise naturally from the form and structure of the music and from the performance etiquette passed down from the generations of people who have performed the folk song or singing game before.

In a community of individuals, knowing and abiding by the “rules” is essential to the group’s survival. People refine their behaviors in order that everyone in the group has a pleasant experience. Because the above rules are inherent in music-making, and because music comes naturally to human beings, it follows that every musical experience gives children natural opportunities to practice community-building behaviors, such as interdependence, friendship, peaceful coexistence, and communication.

People in a community depend on one another. If a child refuses to join hands with another, or if he pulls on the other’s arms, or sings in a loud, disruptive voice, all of the children lose out on the benefits of the experience. Consequently, the child’s relationship to his companions changes over the course of a musical performance or singing game because “he needs his companions more; he approaches them confidently, he accepts and abides by their wishes” (Forrai 1998). When children make music, they depend on and learn to accept each other. This acceptance creates goodwill among the children as they enjoy the musical experience.

These feelings of goodwill and enjoyment lay the groundwork for lasting friendships. When a child finds in one of her companions a good dance partner, for example, she feels happy having found someone she can trust, someone who matches her movements and enthusiasm. In that way, “friendships are formed” (Forrai 1998). When the child is called upon during a song or singing game to be that good partner, she approaches her companions with amicability and confidence. Not only does each child find friendship among his peers, but the whole group develops a positive relationship with their teacher as they share the excitement of the game (Forrai 1998).

As the children form friendships during a singing game, the relationship between the individual children and the group takes on a special meaning. When child participates effectively, her newfound skills give her a sense of belonging. At the same time, the other children develop greater respect for that child if she “can sing in tune and is a good organizer” (Forrai 1998).

Those who rebel against the will of the collective, on the other hand, by walking the wrong way or singing in a funny voice are easily corrected and redirected by the group in accordance with the demands of the song. During music games it’s easy to get positive feedback when the child participates as a valued member. Others smile at him, sing with him, harmonize with him and imitate his movements. The child’s impact and role in the group is clear. In sum, “the child who has enjoyed taking part in an activity easily finds his place in the group and is happy to play with the other children” (Forrai 1998).

It turns out that the key to building community and the key to making music are one and the same: communication. Children learn valuable communication skills when they take part in musical activities.

As the teacher explains the rules of a song or game, the children practice listening and following directions. Often, they have to do so at the spur of the moment, such as when a “caller” calls out motions to perform during a square dance. Children watch people and imitate their gestures during imitation games. Whenever children are called upon to switch partners, they alternate between taking charge and leading or stepping back and letting themselves be led.

Through music games that involve role play, the child’s “emotional world becomes richer, more varied, deeper” (Forrai, 1998) and he learns to express his feelings. Give him enough experiences to play different characters and express different emotions, and before you know it the child will lay the corner stone for community-building: empathy.

MUSIC IS ACADEMIC

Be that as it may, people often emphasize music’s importance in affective terms and forget that “music develops the child’s intellectual faculties. [It] brings the child’s cognitive abilities into play” (Forrai 1998). Who hasn’t run into this bias before? A consultant or administrator walks into a busy classroom where music is thriving and asserts that the musical activity, although undeniably fun, was ultimately distracting to those children who were trying to engage in “academic” work. It’s a cliché among educational circles of all stripes to draw a line between “the arts” and “academia.”

The fact is that music is academic. Music exercises more parts of the brain than almost any other single activity. Just listening to music helps children, especially those with learning difficulties, to access parts of their brains that function poorly or not at all (Foran 2009). Work on music achieves many of the same cognitive goals as any of the other work in the classroom.

Specifically, music helps develop the child’s memory (Forrai 1998). While work in music may not help the child to memorize his math facts per se, a math equation has but one solution, whereas a song has a melody, a structure, a series of gestures, and multiple stanzas full of words for the child to hold in his mind, not to mention a whole host of memories associated with the joy of performing or listening to the song.

According to an article by Lucille M. Foran, “Research has shown that children with high levels of music training have an increased ability to manipulate information in working and long-term memory” (Forai 2009). Indeed, when a child learns a song, he memorizes a rich variety of complex stimuli. In a call-and-response, or echo song, a child’s short-term memory is exercised as he recalls the words, melody and gestures that he heard only moments before. In a larger scale song, such as a folk ballad, the child’s long-term memory comes into play to help him learn multiple stanzas.

Some song structures require the child to memorize multiple stanzas as well as a refrain. When a child revisits a song at a later time, he remembers not only the words, melody, and movements of the song, but he also might remember who he played the song with, how much fun he had playing it, even what the weather was like when he played the song. Even babies as young as 8 months have shown the ability to recognize a familiar piece of music after a two-week delay (Parlakain Lerner 2010).

What’s more, songs can be presented in different forms to trigger the child’s memory. You could take a familiar folk song and hum the tune, tap out the rhythm, or sing a little bit of the song and that would be enough to spark the child’s memory. Indeed, “as a consequence of an organized aesthetic experience, a single rhythm, movement or word may recall [the] entire song” (Forrai 1998).

Plus, when the child hears that single rhythm, melody, or sees that movement, he can remember a wide range of things about not only the song itself, such as its key or the structure, but also his experiences performing it. When was the last time you remembered all those things when presented with a math fact?

In addition to developing the child’s memory, singing and performing musical games and songs stimulates the child’s imagination, especially when child is immersed in musical situations in which he acts out roles and creates an imaginary world (Forrai 1998).

The game that accompanies the Anglo-American folk song “Oats and Beans and Barley,” for instance, calls for one child to stand in the middle of a circle of singing children and mimic the movements in the lyrics. Everyone uses their imagination as the child in the middle takes on the role of the farmer, scattering his imaginary seeds and standing with his thumbs tucked into his imaginary overalls (the apparently universal gesture for “farmer”).

During a game played to the tune “Green Grows the Willow Tree,” the children stand in a scattered formation pretending to be trees while one child wanders among them. When the wandering child touches one of the “trees”, that tree morphs into a human companion for the child, and the two sit on a bench and watch the rushes sway by the river, until the first child herself become a tree, leaving the second child alone to wander the “forest” and repeat the cycle. This game invites the children to not only take on a role, but to change roles, all the while using their imaginations to transform the everyday world of the classroom into a rich, fantastic magical forest.

At the same time that music develops the child’s memory and imagination, it also enhances thought processes, such as recognizing differences, logical thinking, pattern recognition, and math skills. During his musical experiences, for example, the child encounters concepts in opposite pairs like fast and slow, loud and soft, long and short. Comparing opposing pairs aids in the formation of concepts as the child observes, comments on, and analyzes their differences (Forrai 1998). The ability to perceive the parts of a song which are same or different helps the child recognize patterns, which is critical for building early math and early reading skills (Parlakain Lerner 2010).

When the child is confronted by the inherent logic of the song or game and must conform to its unspoken rules and etiquette, or when he perceives the structure of a folk song or piece of music, and holds it in his mind, he also develops logical thinking. A child refines his logical thinking and reasoning skills when he modifies the words in well-known songs or asks other children to fill in the blanks in singing, such as in the song “[Dante] had a little [fish], whose fins were bright and orange” (Parlakain Lerner 2010). Further, “Current brain research reveals that the audition of [music] may increase spatial intelligence or the ability to form accurate mental images of physical objects” (Marchak 1998).

It’s well known that music benefits the brain because the form and structure of the sounds and the pattern of the melodies suit our mathematical mind. Many songs, for example, include counting, such as “One, Two, Buckle My Shoe”, “Five Little Monkeys”, and “The Animals Came in Two by Two”. They rhythm and repetition in songs helps children to recognize number patterns (Parlakain Lerner 2010).

Speaking of the mathematical mind, music also paves the way for abstract thought. When a child perceives tones as occurring on a vertical high-low spatial axis, when he talks about the “beginning” or “ending” of a song, when he describes fast, active sound wave vibrations as “high”, he is using abstract thinking skills (Forrai 1998). Because, unlike other arts, music doesn’t exist until it is recreated by the child and perceived by the other children, the child and his audience must form an abstract understanding of the piece being sung, composed, or created.

But if you ask which area of development music benefits the most, the majority of people will mention language skills. “By engaging the cerebellum, the motor cortex, and the frontal loves [of the brain], music…plays an important role in language development” (Foran 2009). Music helps children with language and literacy skills in multiple ways. For one, music gives children an easy-to-enter window into practicing language and deciphering meaning (Parlakain Lerner 2010).

Long Anglo- and African-American folk ballads, such as “Sweet Betsy From Pike,” contain colloquial words and references from the American pioneer days, inviting children to make meaning from words used in a different time and culture. The Spanish folk dance “El Gato y el Raton” allows children the opportunity to travel and immerse themselves in a different language and culture.

Offering music in a child’s home language supports dual language development, especially during the first six years, when the child is in her sensitive period for language (Parlakain Lerner 2010). Even singing in languages unfamiliar to the child, or singing nonsense songs, helps the child to make meaning from words, especially when the melody or the music contains a certain emotion.

In the lovely, minor-key song “La Mar Estaba Serena,” a group of sailors find themselves trapped at sea adrift on a raft during a rainstorm. Singing the sad melody and acting out the part of freezing castaways, the children can’t help but decipher the meaning of the song’s lyrics.

Even rhyming songs benefit the children’s language skills. When children learn to sing and participate in songs that rhyme, they develop phonemic awareness, which is how well a child can hear, recognize and use different sounds. Children who experience regular participation in music that rhymes are able to distinguish different sounds and phonemes and are therefore more likely to develop stronger literacy skills over time (Parlakain Lerner 2010).

What’s more, because the child must be an active participant in the experience of making or listening to music, his general cognitive development is enhanced. He is an active learner, throwing mind, body, and senses into the song or game. Indeed, the best part about music is that it generates feelings that spur the child on to further activity.

Dr. Montessori said that “Knowledge can best be given where there is eagerness to learn” (Montessori 1991). Work in music definitely sparks the child’s eagerness to learn. Whether his musical experience involves dancing and singing or just listening, the child wants to repeat these musical experiences and to relive his enjoyment by singing to himself, organizing games, suggesting songs to the teacher, or inviting his classmates to sing (Forrai 1998).

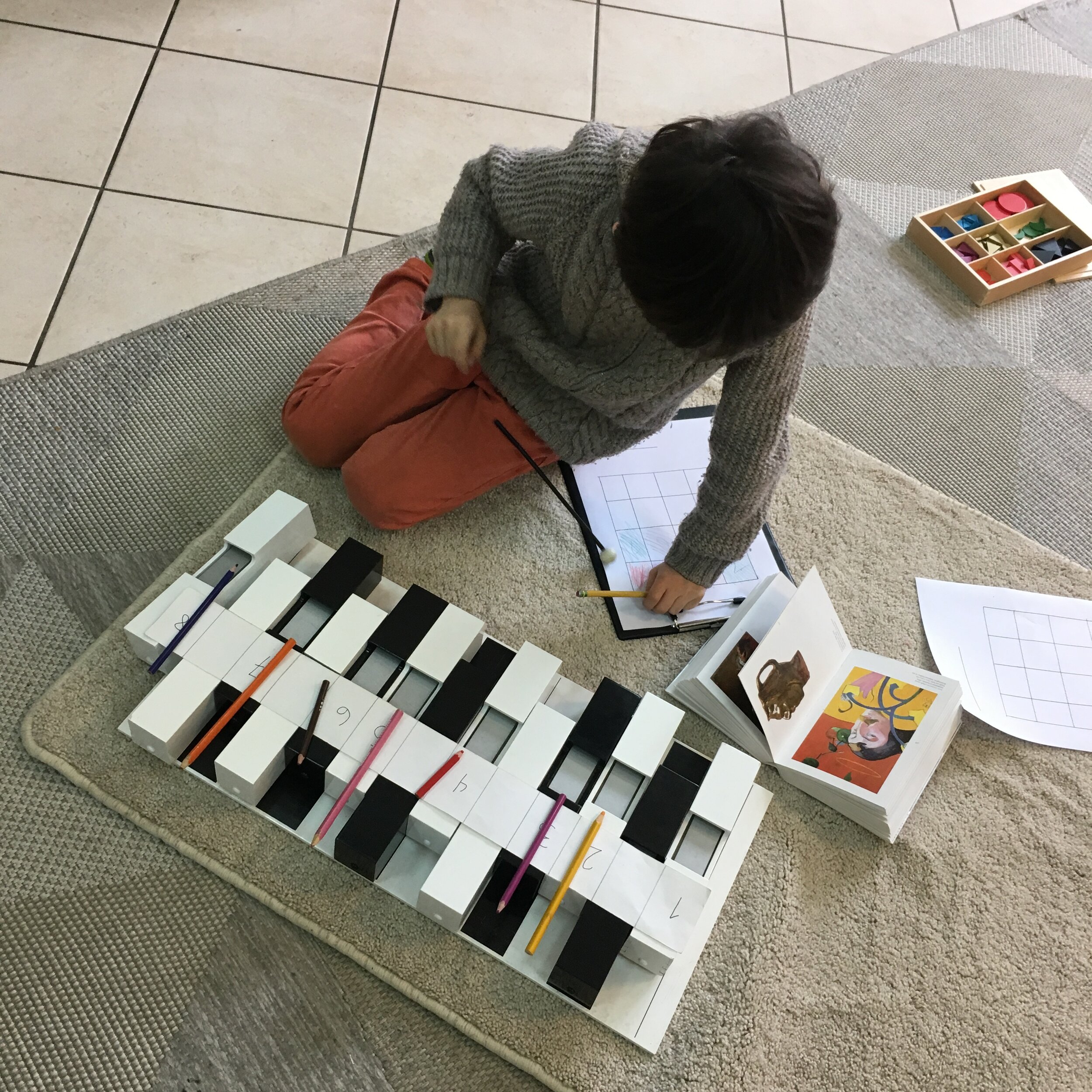

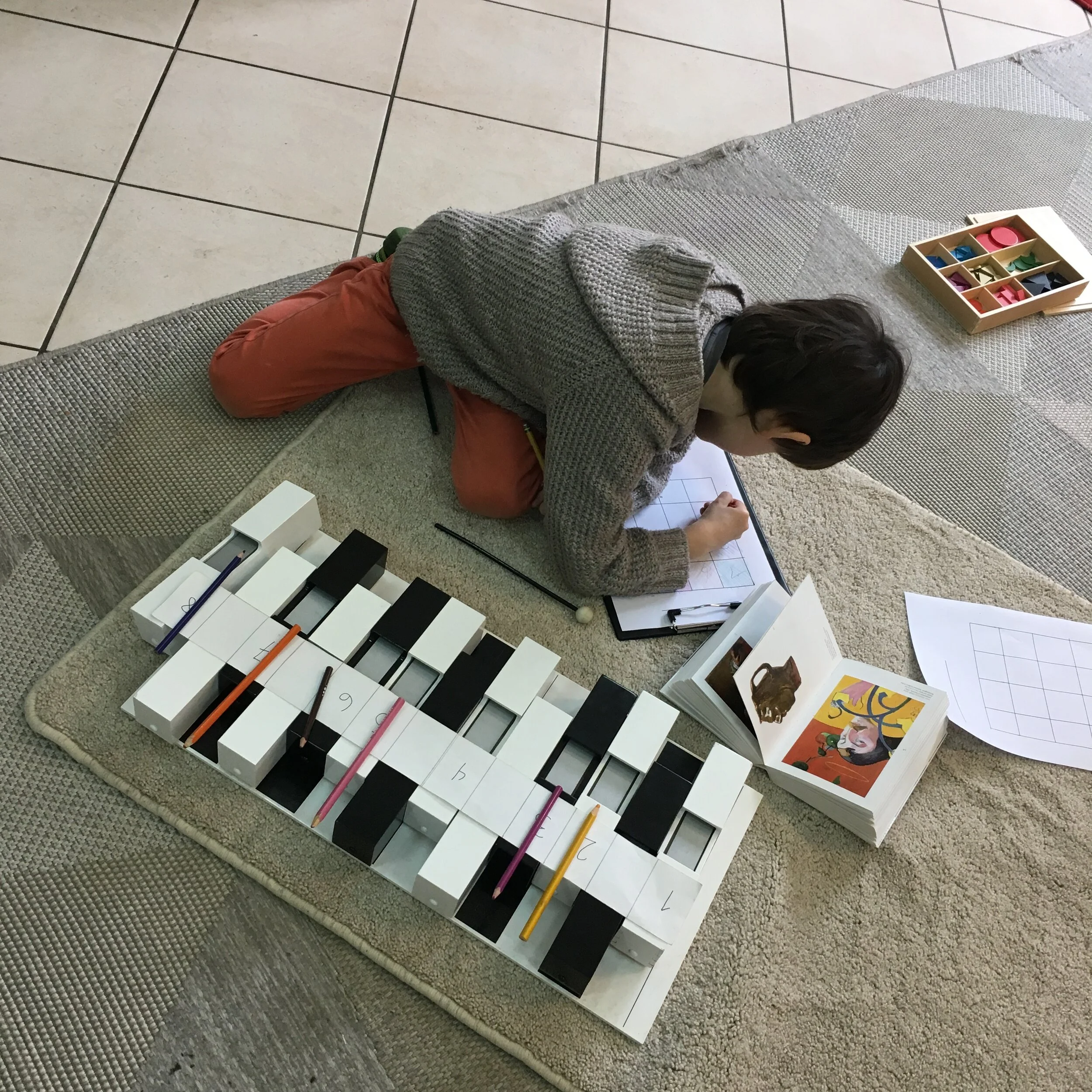

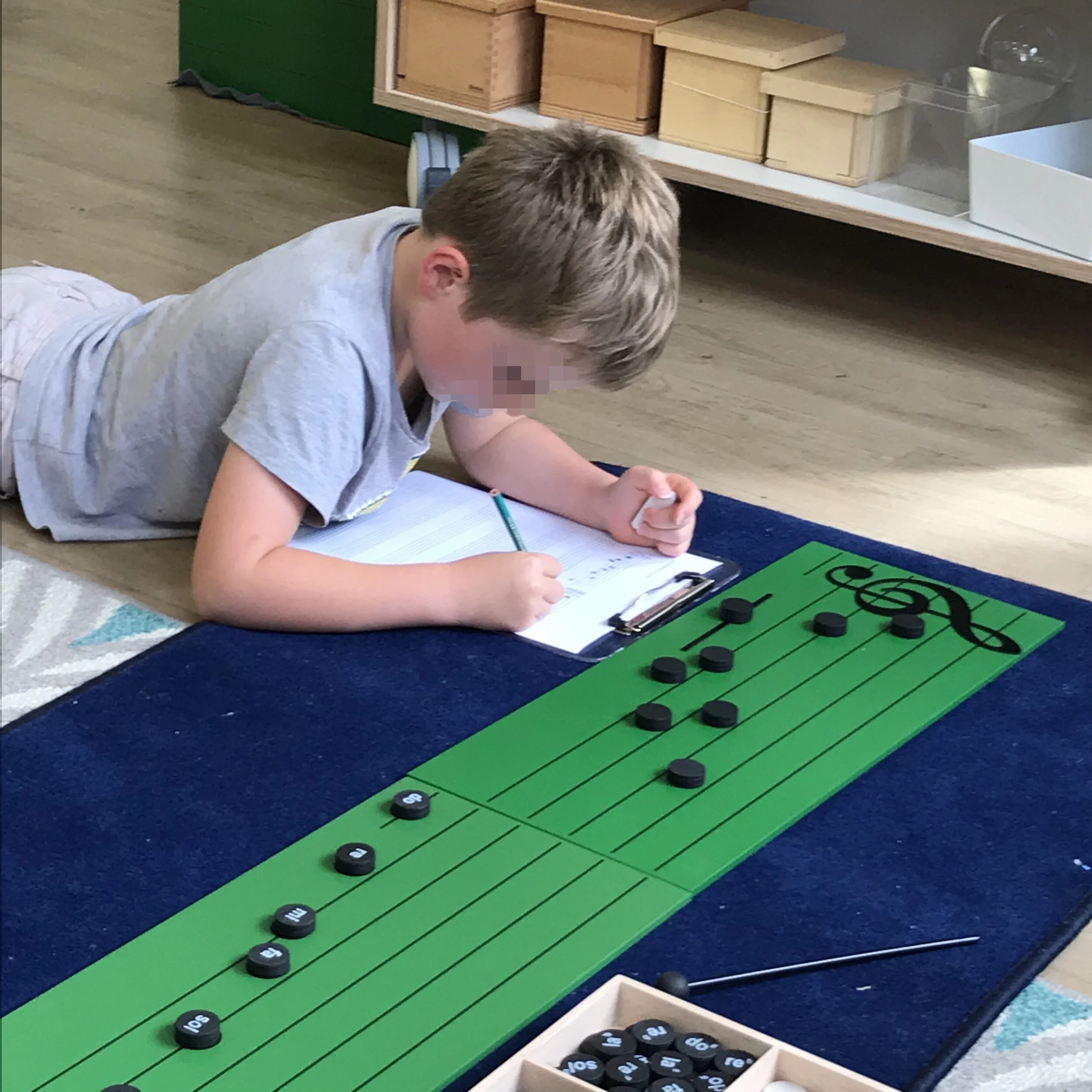

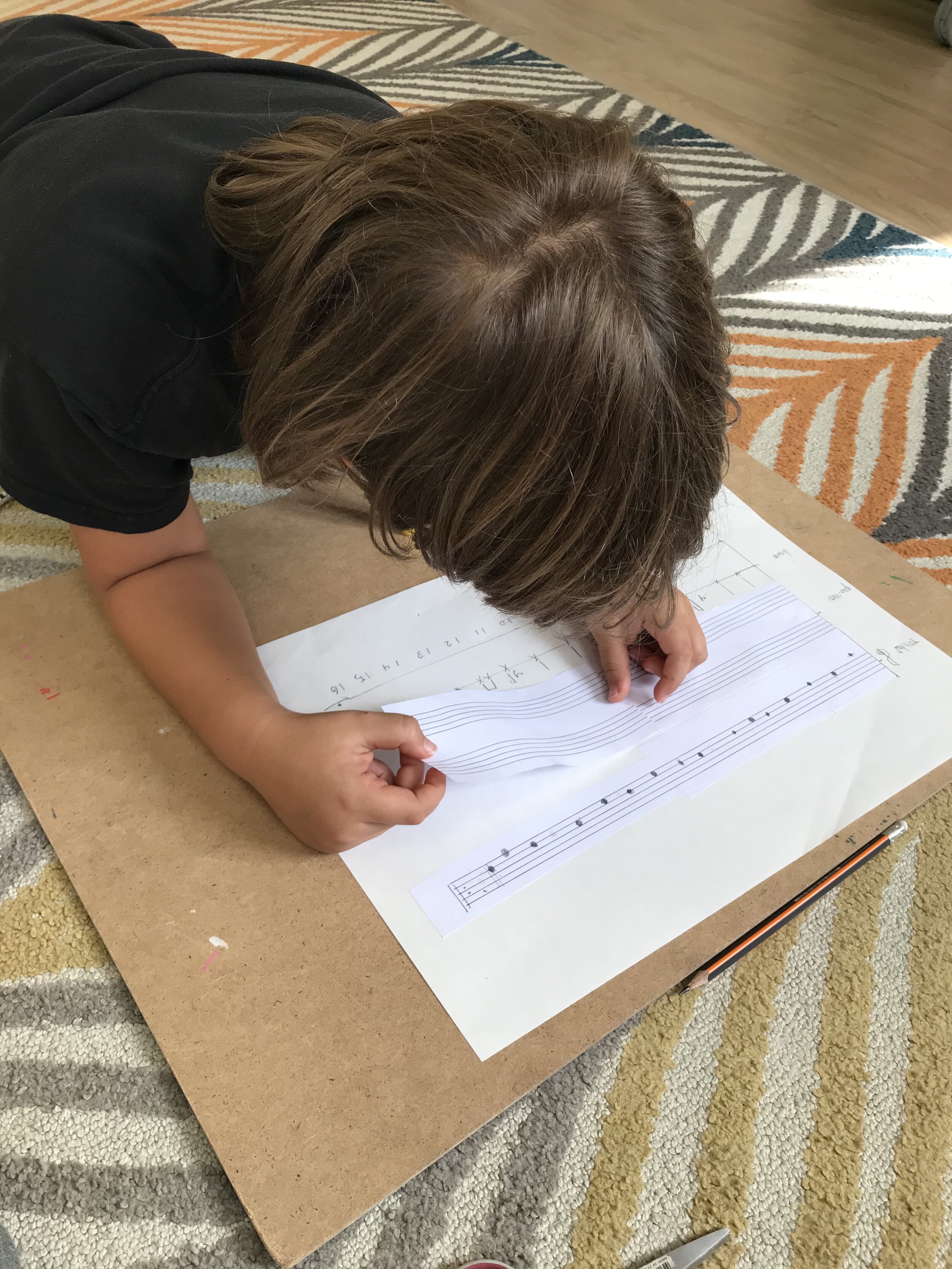

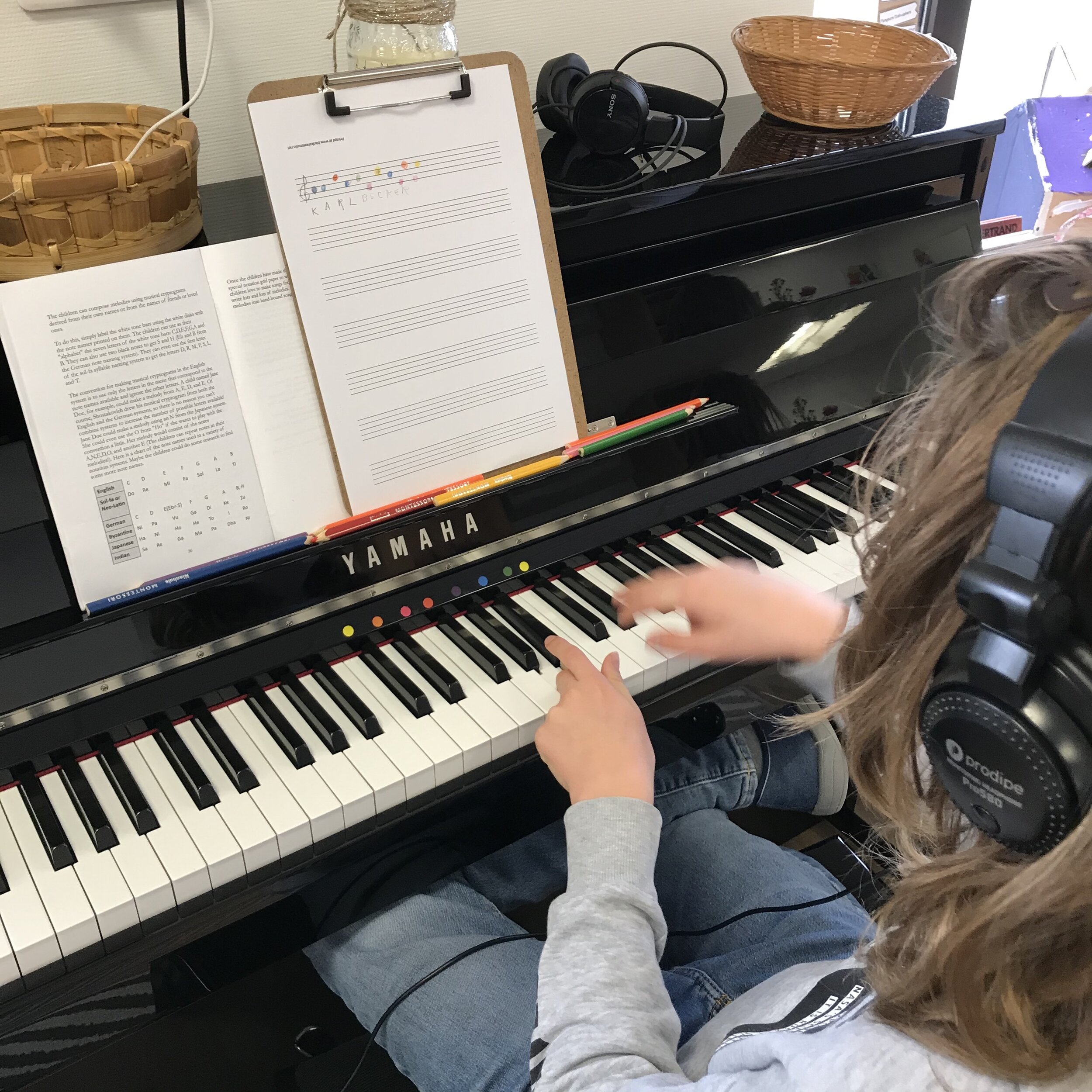

The child finds inspiration in Cosmic Stories about composers or about the history of music and wants to listen to that composer’s music, or create his own original music. If a piano lives in the environment, the child wants to touch it, to play it, to experience the enjoyment of making sounds herself. Music becomes an academic discipline that the child wants to experience again and again.

MUSIC IS GRACE & COURTESY

Yes, you read that right: a piano. You may be thinking that having a piano in the classroom proves a recipe for chaos. After all, from an adult mindset, a piano is an easy outlet for a precocious child.

The bored child, after all, can press lots of keys down at once, bang on the keys with her fists, elbows, or forearms, or play “Heart And Soul” until everyone in the room becomes driven to distraction. A piano makes sound, and sound is distracting.

But by bringing a piano into your classroom, you send even the most precocious among your children the message, “I trust you. You will care for this musical instrument and use it responsibly. You will use it to beautify our classroom with wonderful, not distracting, sounds.”

After all, every object that we add to our environment comes with freedoms and responsibilities. Why should a piano—or any other musical instrument for that matter—be any different? As Plato said, “The most effective kind of education is that the child should play among lovely things.” That big glossy black box with its pretty white and black keys, each of which rewards the child with the instant gratification of a beautiful sound, rules the Kingdom of Lovely Things.

“Ah,” sayeth the voice in your head, “but handling such a fine object responsibly is too great a challenge for a child.” Answereth this author: “A child needs opportunities to rise to that challenge.”

The piano is that opportunity.

In order for your small practice society of children to meet the challenge of having a piano, however, they must first recognize that the piano carries with it certain freedoms and responsibilities. Suppose any child has the freedom, for example, to choose the piano as a work choice. The responsibility that balances that freedom is that the child must actually work.

Work at the piano might mean bringing in literature from the child’s lessons outside of school and practicing her repertoire, or composing at the piano for follow-up. Work could also mean playing a duet with a friend. Maybe a child wants to play the right-hand part for “Heart and Soul” and teach another child the left hand part. This also constitutes work.

Playing random noises, mindlessly repeating the same song, acting silly at the piano with a partner, however, are not responsible uses of the children’s freedom to play the piano.

Second Plane children, with their sensitivity to fairness and justice (Travis 1999), embrace this distinction. Once the children understand their freedoms and responsibilities, they can work to develop for the classroom some rules of piano etiquette.

Etiquette for the piano begins with the question of when the piano could be played. The children could establish a rule that anyone could play piano during the work cycle, provided it doesn’t disturb anyone. As soon as the piano gets to be distracting, a child may walk up to the pianist and politely ask him or her to close the dust cover. If that happens, the child playing piano has to stop, no matter what, and both children have to find other work. This bit of etiquette will likely come from the children after a fruitful discussion.

In fact, the children love opportunities to come up with new rules of etiquette. This should come as no surprise. After all, in Montessori environments “[The children] often establish their own rules, their own code of ethical behavior…”(Travis 1999). This is as true in music as it is in any other area of the classroom. Other rules of etiquette the children came up with can center around how loudly the piano should be played, how many people should sit at the piano at one time, etc.

So, you see, as adults, we shouldn’t fear pianos in our classrooms, for along with the piano comes an opportunity for the children to discuss, debate, and craft a whole set of new rules for their tiny society.

It’s one thing to establish etiquette for the piano, but children in the Second Plane will also need to know the reasons why such etiquette should be in place. The reasons to have piano etiquette ought to be simple. Allyn Travis writes, “Sometimes the reason a certain courtesy is expected is as simple as the fact that this is how we show respect for another human being (Travis 1999).”

Respect with regard to the piano means making sounds that are beautiful, sounds that blend into the atmosphere of the classroom, sounds that sit in the background of the colorful tapestry of sounds in the classroom, sounds that don't distract or annoy the other children. When a child plays the piano during the work period, like a violinist on the Esterhazy estate accompanying one of the prince’s feasts, she shows utmost respect by humbly providing a service, lending her talents to the ambiance in the room.

Further, she models deference to the other children and inspires the other children to want to play. She shows her respect for the other children by being mindful of how her music affects people’s work. If another child comes to her to ask her to stop playing, she shows respect by gracefully complying. If a child is already playing the piano when she wants to play, she shows respect for that other child, and for the rest of the children, by waiting her turn.

When children are aware of the reasons why they must comply with classroom etiquette, when they understand this level of respect, they rise to it. What was before just a classroom with a piano transforms into a hallowed space where children make music to benefit their own “spirit” and the “spirit” of every child in the room.

Should the children sit down at the piano to play and renounce the rules of etiquette, as many adults convince themselves they will, we can take comfort in knowing that their “spirit” is not completely in danger, for, in Montessori we have some quick lessons that serve as provenders of the “spirit" which we call Grace & Courtesy.

Once the children establish etiquette for the piano, you can design a unique set of Grace & Courtesy lessons specific to the piano. Such as:

• How to invite a friend to play the piano with you.

• How to accept or decline such an invitation.

• How to quietly raise and lower the dust cover.

• How to quietly position the bench.

• How to get help positioning the bench.

• How to ask someone to play more quietly or to stop playing.

• How to accept someone’s request that you stop playing.

• How to thank someone for playing piano for our community.

These Grace & Courtesy lessons “catch the child’s interest…using humor and role playing. If [you] show the children through a funny little skit what happens when the [undesirable] behavior is carried out, [you] can catch their attention and involve them in thinking about how the situation could be handled differently so that the results turn out more positive for everyone" (Travis 1999). In other words, “[You] role play doing something incorrectly and have the children show [you] how to do it properly” (Travis 2009).

At the piano, these little skits can be quite funny. One teacher used to demonstrate how not to play the piano by teasing his bouffant into a wild, unruly mess that he and the children eventually dubbed his “composer hair.” Then he sat bolt upright on the bench, tucked in his upper lip, jutted out his chin, made a face like he was sniffing manure, and banged out the most abrasive, outrageous, deafening chord he could manage. When the children’s laughter died down, they articulated the drawbacks of such behavior.

These little humorous role play lessons are not the only times when children can learn Grace & Courtesy, because they play an important part in many of the songs, singing games, and role plays that the children can perform together. When two lines of partners dance together in a French folk song like “Sur le Pont d’Avignon,” the niceties of bowing and curtseying must be observed.

When a child takes a partner in the Anglo-American folk song “Bluebird, Bluebird,” or bumps hips, shake hands, and hug during the African-American song “Shoo-Rah,” they learn to treat each other with respect and kindness, to give and take, to be a leader or accept someone’s leadership, to abided by each other’s wishes, and to go with the flow.

In short, music affords the children wonderful opportunities to “develop kindness, respect, humanity, good will, altruism, mercy, charity—all synonyms of the word grace—as well as consideration, favor, dispensation, indulgence, service, privilege—synonyms of the word courtesy” (Travis 1999).

MUSIC IS EMOTIONAL AND BODY REGULATION

In addition to the benefits discussed above, performing music supports children’s ability to self-regulate. Consider a game called “Grizzly Bear,” in which a circle of children run screaming in all directions after they sneak toward and wake a child pretending to be a sleeping grizzly bear in the middle. You wouldn’t think a game like that could accomplish anything but rile the children up. But to see how even a game like “Grizzly Bear” is beneficial to the children’s ability to manage their emotions, control their bodies, and develop valuable social skills, let’s agree on what “self-regulation” means and what it looks like.

Self-regulation, the term that refers to a child's ability to manage “one’s emotional state and physical needs” (Parlakain Lerner 2010), “is critical to a child’s mental and physical health. Healthy emotional regulation is connected with higher academic achievement, lower levels of negative emotionality, higher levels of empathy, and higher levels of social competence” (Foran 2009). On the other hand, failure to self-regulate has been connected with later diagnoses of major mental illnesses, including psychosis, borderline personality disorder, and drug and alcohol abuse, among others (Foran 2009).

According to an article by Kate E. Williams, the skills children need for self-regulation come in three varieties: emotional regulation, attentional regulation, and executive functions. Emotional regulation skills encompass the extent to which a child can move back and forth between heightened emotional states and states of equilibrium, or calm. Children who can easily find calm and composure after being excited or upset have learned emotional regulation skills. Attentional regulation skills are required for children to proceed with a task when there are distractions present. A child who can stick with a difficult task or return to the same task after taking a break has good attentional regulation skills.

Considered to be the higher part of the human self-regulatory system, executive functions control a child’s behavior and cognition. Executive functions are especially relevant to music because they consist of the specific processes of memory, inhibition, and mental flexibility. You’re already read about the benefits of music on short-term and long-term memory. Working memory is a child’s ability to actively maintain information in short-term storage for use in executing a specific task. Children display working memory skills when they perform an ordered series of movements, such as patting the knees, clapping once, and then clapping their partner’s hands.

Inhibition refers to a child’s ability to inhibit behavior as required at a particular moment. A child with good inhibition skills can wait for a cue before touching an instrument, refrain from calling out randomly during a song or game, or wait for a cue before touching a body part during, for example, a game of Simon Says.

A child displaying flexibility can switch her attention or cognitive set between distinct or related aspects of a given object or task. A flexible child can, for example, hear a melody and focus on the words, ignoring the melody, then hear the same melody and focus on the melodic contour, ignoring the words (Williams Lewin 2014).

As it turns out, during a performance of “Grizzly Bear,” the children exercise self-regulation skills in all of the above areas. After the children run screaming from the grizzly bear trying to tag them, they must calm down again in order to select a new grizzly bear and proceed to quietly sneak up on it. A child committing to the role of a sleeping grizzly bear while all of the other children sneak toward you trying to suppress giggles displays attention regulation skills.

In a performance of “Grizzly Bear” the children develop their executive functions as well. They work on inhibition, for example, when they commit to their roles and resist the urge to make extra movements or do something to inhibit the game. Singing the melody of the song once, being chased, calming down, and then singing the melody again requires the children to flex their working memory muscles. And finally, switching attention from the entire group singing the song’s melody, to running from the grizzly bear, and then focusing back on the whole group, as well as keeping track at all times of where everyone is in the song, was an exercise in flexibility.

You can see that active music participation increases children’s self-regulatory functioning (Williams Lewin 2014). Studies corroborate this assertion. Children in a study conducted in 2011 by A. Winsler and colleagues were given a battery of tasks that required them to demonstrate self-regulatory skills such as waiting, slowing down, and initiating or suppressing a response. The group of 3-to-4-year-old children receiving weekly Kindermusik music and movement classes showed better self-regulation skills than those not enrolled in any structured early music classes (Williams Lewin 2014). Furthermore, arts-enriched preschool environments that include music have been found to improve emotional regulation skills in low-income children when compared to non-arts enriched programs (Williams Lewin 2014).

In addition to self-regulatory skills, participation in music helps children with so many other much-needed emotional, body, and cognitive development skills. Below, you’ll find a breakdown of the additional emotional, body, and cognitive development skills that the children practice during a single musical performance.

Emotional, Body, and Cognitive Development Skills Practiced in a single Singing-game Performance

EMOTIONAL, BODY CONTROL, AND COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT SKILLS PRACTICED IN A SINGLE SINGING-GAME PERFORMANCE

Socio-emotional Domain

socio-emotional skills

The children share with each other the experience of singing, moving, and playing roles together. They encourage their fellow participants by chasing and tagging and committing to the role. They communicate with each other, helping each other be aware of where the group is in the song.

understanding emotions

The performance evokes feelings of joy, of fun and connection with their fellow classmates.

cooperation and relationship building

The performance is a team effort. Every child has a specific role that contributes to the success and enjoyment of the experience. All during the piece, children switch from actively singing and moving to running and being tagged. The children develop friendly attitudes toward each other as they appreciate each other’s performances, cooperate, and drop their inhibitions.

Self-esteem, self-confidence, self-efficacy

Playing a grizzly bear, the children develop a sense of confidence as they express movements and ideas in front of the others. They feel that they are “capable”, and “smart” as they sing with one another within the fabric of the piece. They feel that they have something valuable to contribute to the performance.

sharing and taking turns

The children take turns being chased and being the grizzly bear. They accept their fate when they are tagged. They enjoy being the center of attention as the grizzly bear and they enjoy blending in with the crowd when they are waking the grizzly bear.

cultural awareness

Before the performance, the children are given a brief story of the history of the song and its cultural origins.

Physical (motor) Domain

gross motor development

The children use the muscles in their legs and trunk to run, to imitate the grizzly bear sleeping, to jump up and chase the others. They express their joy by clapping and calling out.

fine motor development

The children use the muscles in their lips and mouth to sing the song’s melody. They use the muscles in their fingers to hold each other’s hands while creeping up to the grizzly bear, or to make shushing motions by raising an extended index finger to their lips.

balance

The children move their bodies to the music, stepping to the beat as they sneak up to the grizzly bear.

body awareness

The children are careful not to collide with others as they run from the grizzly. They respect each other’s personal space.

bilateral coordination (crossing the midline)

The children may clap to the beat, which requires crossing the midline to join the hands together. Percussion instruments, such as a guiro, triangle, or tambourine can also be added to the song.

Cognitive Domain

counting

One child “counts in” to begin the performance, saying “A-one, a-two, a-one, two, three, four…” The children count internally as they step to the beat of the song. They count how many steps to walk in a circle with joined hands before turning inward and walking toward the grizzly bear in the middle.

steady beat

The entire group agrees on the pulse of the basic beat. Children may play the beat on percussion instruments, pat the beat on their knees, or clap their hands to the beat.

memory

The children hold in their minds the melody of the song. They form a mental impression of the structure of the song. The performance creates joyous memories. The children sing the melody after the performance is over.

discrimination or observation of differences

The children perceive the loudness of the moment when everyone shouts “Mad!” or softness of the moments when everyone is sneaking up to the grizzly bear. They perceive differences in the timbre and tone of the various instruments used during the performance.

pretend play and symbolic thinking

The children take on the role of “grizzly bear” or “doomed camper” as they either pretend to sleep or sneak around in a cave trying not to wake the bear.

With so many prosocial and cognitive benefits of music making, it’s a wonder more Montessori teachers aren’t making music in their classrooms.

MUSIC IS “COSMIC EDUCATION”

Recall that the Montessori curriculum comprises “the whole universe, its furnishings, its inhabitants, and all of their stories” (Travis 2009). Music, the language of all human beings everywhere, is a part of that universe. We can’t leave it out. In her book To Educate the Human Potential, Montessori writes, “we see no limit to what must be offered to the child, for his will be an immense field of chosen activity” (Montessori 1991). This all-encompassing approach is what Montessori called Cosmic Education. Let’s briefly review what we mean by Cosmic Education.

In a lecture on given in 1976, Mario Montessori sums up his mother’s plan for Cosmic Education. He says, “We believe that in the cosmos there is harmony; that everything there is in it, both the animate and inanimate, have collaborated in the creation of our globe, correlating in doing this, their single tasks. But we think that among the innumerable agents which participated in this creation man has had and has a very important task” (Montessori 1976).

From this statement we can glean two important things. First, that everything that exists, from the tiniest quantum particle to the most massive black hole, contributes to help the universe subsist and is, therefore, interconnected. Second, that within that interconnectedness, human beings have a very special place. Perhaps, even, human beings have an even higher place than any other agent of creation in the universe. Mario says, “[Man] has detached himself from nature to create—with his work—something above it, a supranatura” (Montessori 1976).

So, an important component of Maria Montessori’s plan of Cosmic Education is to make the child aware of the interconnectedness of all things and of human being’s special role in the shaping of not only the make-up of the universe, but also its fate. I can think of no better subject than music for accomplishing these aims.

If “The trick with Cosmic Education is to highlight how the subjects are interconnected and interlinked” (Travis 2009), then when it comes to music our task is easy. Music is intimately intertwined with all of the other subject areas in our curriculum.

I’ve already mentioned above music’s connection with language and mathematics, but what about history? When we think about composers, performers, and musicians that have come before us, we explore their stories in order to interpret their music. What’s more, music carries with it the sounds of another time, another culture. All music, whether it’s Gregorian Chant or Balinese Gamelan, transmits the sounds and emotions of its era or its culture across time to our ears. When we hear a pentatonic scale plinked out on a koto, we are transmitted to ancient Japan, when we listen to a Bach fugue oozing out of a pipe organ, we can almost feel the high, cold stone walls of the cathedral surrounding us. Music’s link to history is obvious.

Is it a stretch to say music is linked to Geometry? Not at all. If we consider a string, and divide that string in different places, upon plucking it, we find that it resonates at different pitches. Now imagine that that string is a line, and the distances between the points on that line create ratios that represent different musical intervals. The ratio of an octave, for example, is 2:1. In other words, divide a string in half and you get an octave. The ancient Greeks discovered this. It’s almost like magic.

Of course, there’s no magic in it, it’s just the way our wonderful universe works. Is it some kind of sorcery that the interval of a fifth, called perfect, has a ratio of 3:2, which corresponds to the Greek Golden Ratio? The ancient Greeks didn’t think so. Whole structures in music are based on the Golden Ratio. Chopin built his Etudes and Nocturnes around it. Many pieces of music climax two-thirds of the way through. This is the Golden Ratio. An octave can be thought of as a perfect fifth plus a perfect fourth. Once again: Golden Ratio. We also see geometry in the construction of musical instruments. In fact, the geometric shape of the interior of a musical instrument, whether cylindrical or conical, has a deep impact on the instrument’s timbre. Consider the difference between the sound of a flute, which has a cylindrical bore, and a trumpet, which has a conical bore.

What about biology? Can we find a link between music and biology? Indubitably. Musical instruments are made of different kinds of wood, each of which resonates slightly differently, producing different sounds. The sound board of a piano is a thin sheet of wood. When a hammer strikes a string, the sound board picks up on the string’s vibration and, because it's much bigger and can move a greater volume of air, amplifies the sound. Soundboards are often made of spruce, cedar, or rosewood. Guitars, mandolins, violins, and lutes employ soundboards.

Biology is also a source of inspiration for many musicians of the Romantic era. Beethoven, though technically a Classical composer, found inspiration for his Pastoral Symphony (Symphony No. 6) in nature. The symphony tells the story of an artist waking up in the countryside and going for a stroll alongside a brook. The first movement sets the mood and the scene, while the second movement describes all of the sounds and impressions of a babbling brook. In the next movement a storm comes and breaks up a gathering of country folk before the storm passes and everything is cheerful once again.

Many pieces of music were inspired by nature. Olivier Messiaen incorporated bird calls into his work. Camille Saint-Saëns wrote his famous Carnival of the Animals, with its beautiful Swan. From Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, to Rimsky-Korsakov’s Flight of the Bumblebee, to Debussy’s La Mer (The Sea), nature abounds in music.

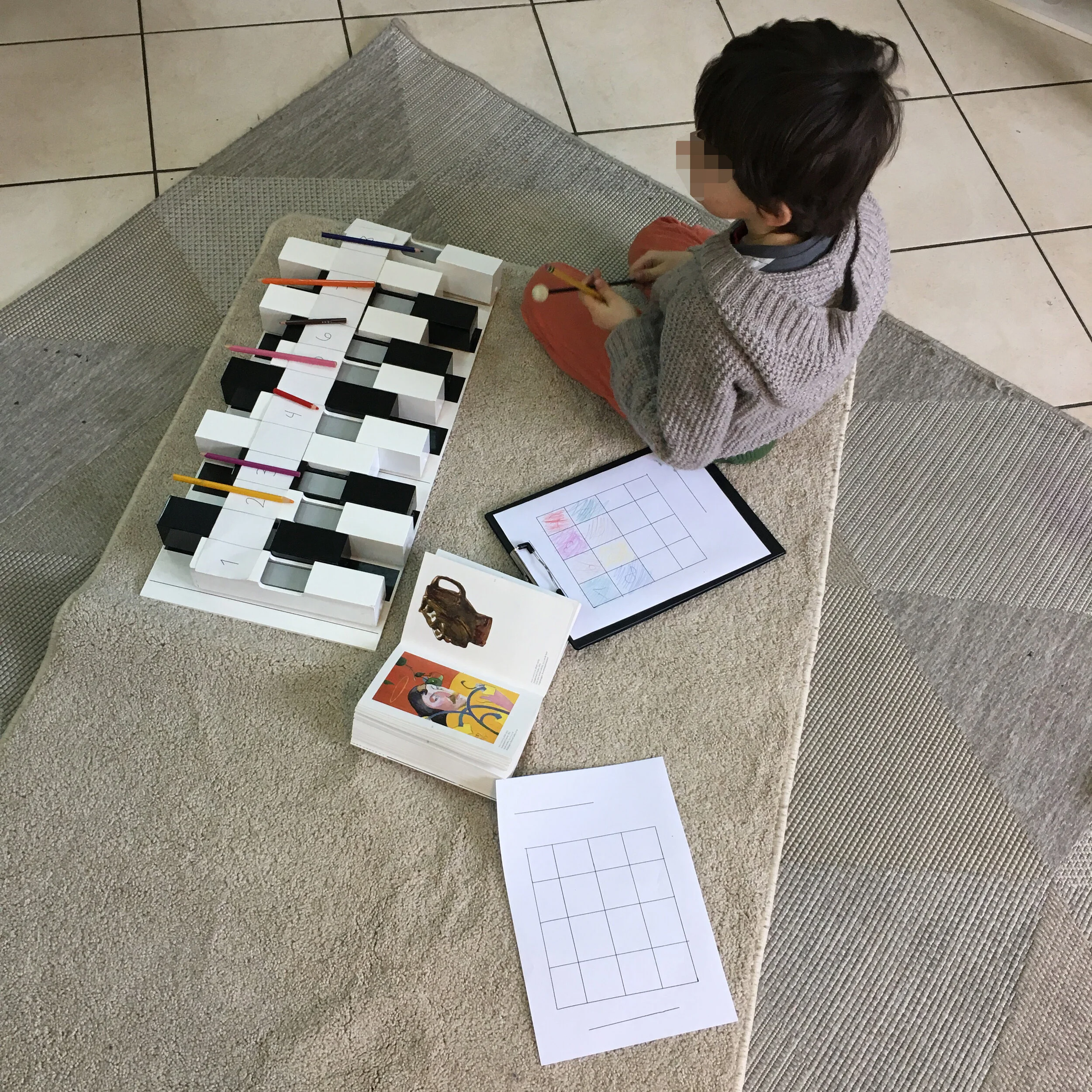

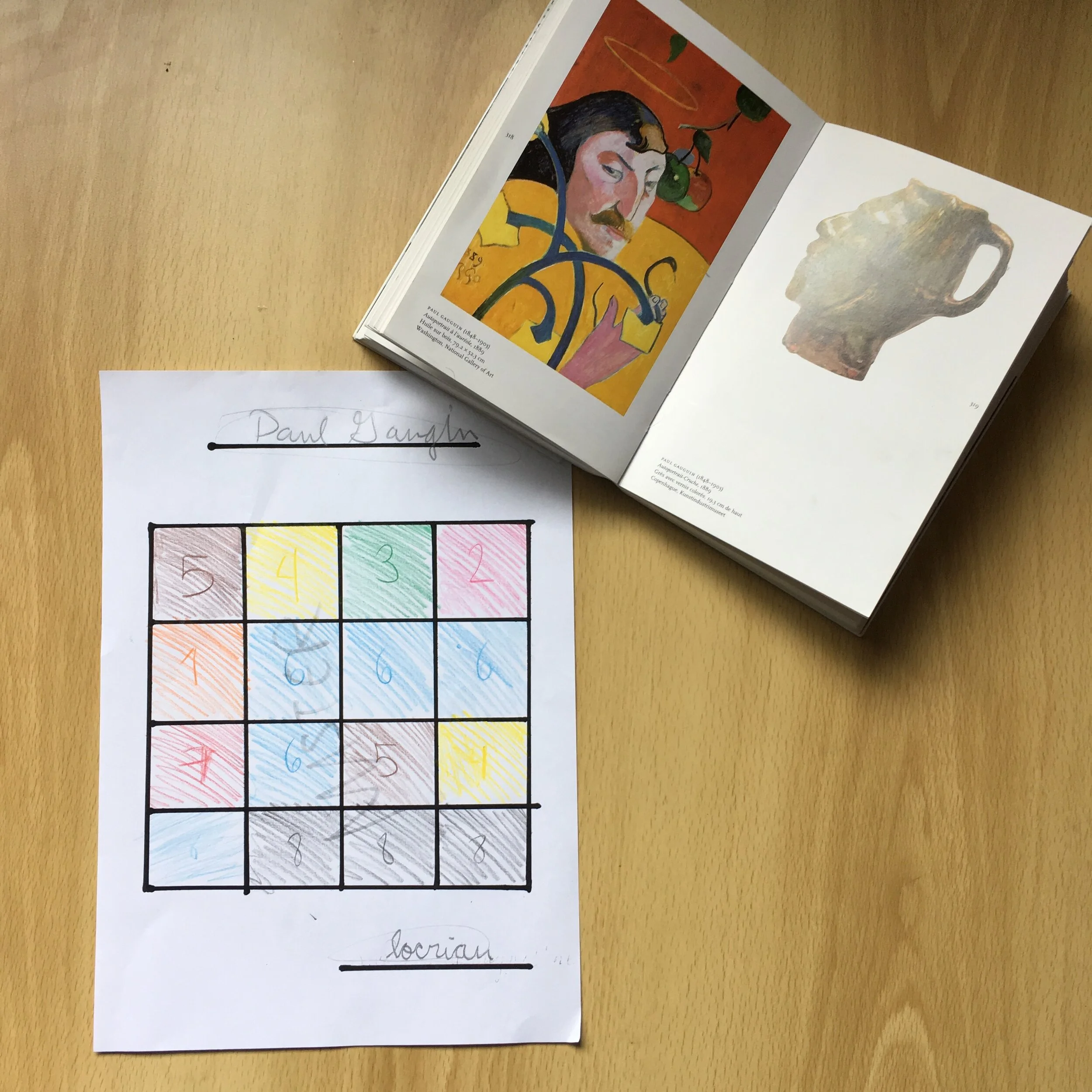

Art and music are intimately connected as well. When we describe tones we often talk in terms of colors. We call a whole genre of music “The Blues.” Many of the most famous musicians, such as Duke Ellington or John Lennon, were also visual artists in their own right. Ellington, in particular, loved to incorporate colors into the names of his compositions, such as “Mood Indigo”, “Black and Tan Fantasy”, and “Magenta Haze” (Venezia 1995).

An entire movement in visual art called Impressionism, in which artists eschewed structure in their pictures and instead sought to capture a particular mood or a particular light, was imitated in music by French composers like Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel, though the former hated having his music described as “Impressionist”. The comparison isn’t entirely unfair, though, as Debussy’s music rejects tonal structure in favor of drifting, aimless sounds that give us an impression of feeling and light.

Musicians often find inspiration in visual art. One of Debussy’s most famous pieces of music, La Mer, is said to have been inspired by one of the most recognizable images in Japanese art: The Great Wave of Kanazawa. The Russian composer Modest Mussourgsky wrote his Pictures at an Exhibition about a spectator walking through a gallery during an exhibition of his late friend’s art. Each section of Mussourgsky’s piece depicts a different painting in the exhibition, and all the sections are linked by a melody depicting the spectator strolling from one painting to the next. Sergei Rachmaninoff wrote his famous Isle of the Dead after viewing a painting of the same name by Arnold Böcklin. A more modern example is Stephen Sondheim’s musical Sunday in the Park With George, a play inspired by Georges-Pierre Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Isle of Grand Jatte.

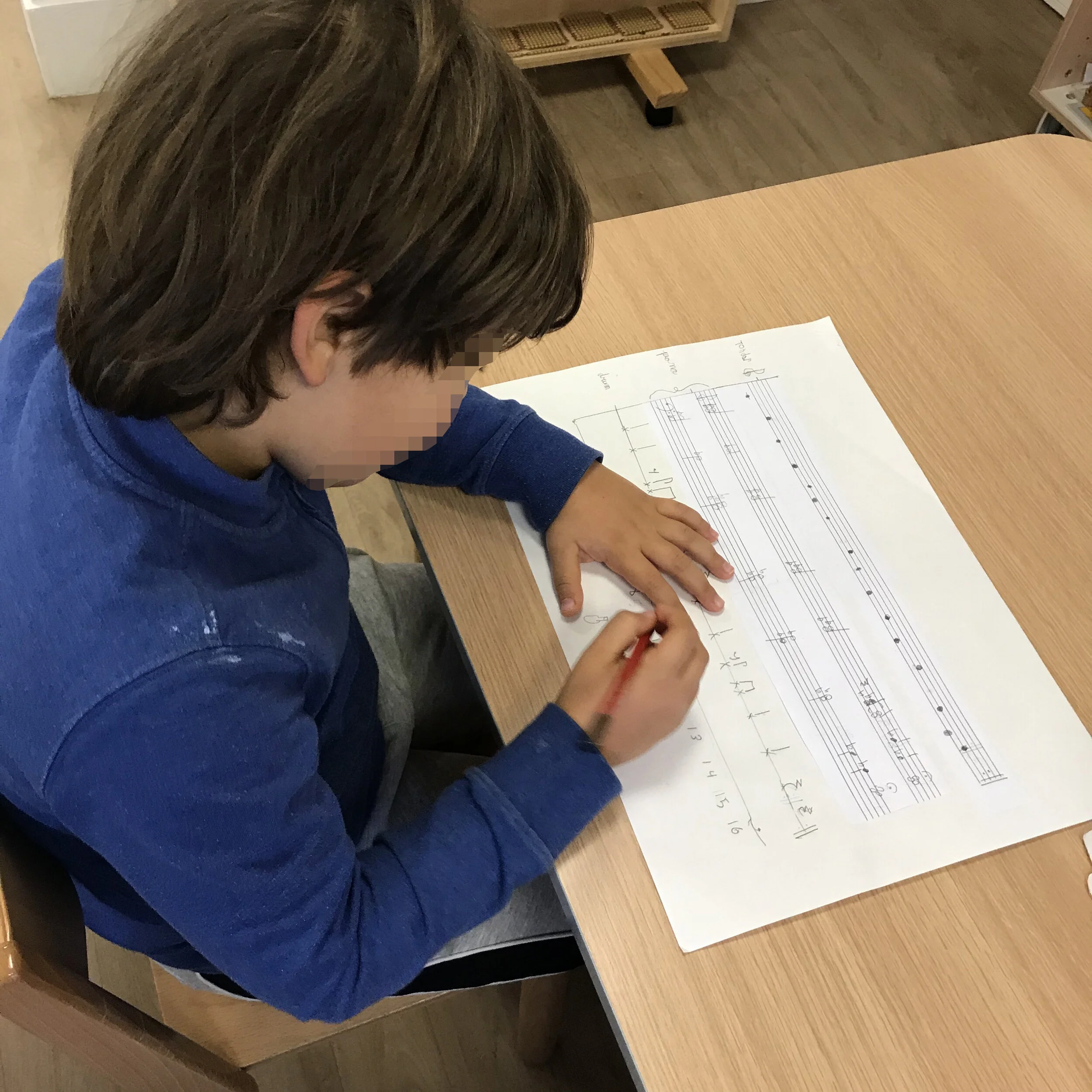

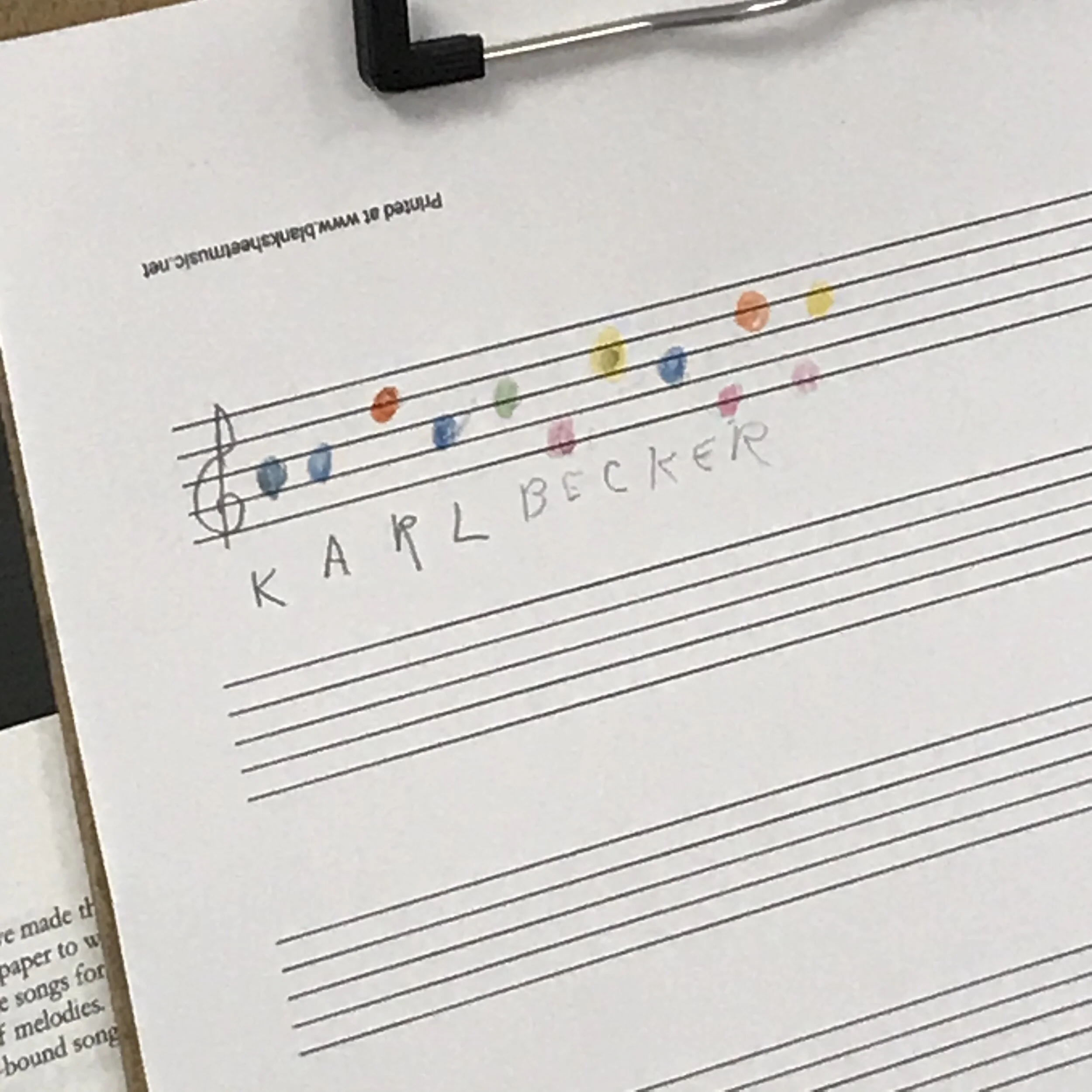

In addition to being inspired by visual art, music notation can itself be visual art. Traditional music notation, with its pretty black and white stemmed ovals and its waves and contours, is pretty enough, but in the 20th century, composers began to experiment with other ways to get their ideas across. Instead of notes on a staff, composers used shapes, colors, lines, or combinations of all three to create visually arresting scores that, although they “made life difficult indeed…for composers and conductors” (Evarts 1968), were compelling to look at.

As new sounds, such as electronic tape and synthesizers, were incorporated into the orchestra, so there arose new methods of notating those sounds. Compositions by John Cage, Steve Reich, Brian Eno, and Karlheinz Stockhausen, among others, are just as notable for the graphic layout of their scores as they are for the sounds they represent (Stamp 2013).

In an article in the art and music journal Leonardo from 1968, John Evarts writes of the musical notation of his contemporaries, “Perhaps within a few years these picturesque squiggles, graphs, and fantasies will be considerably more admired for their visual appeal than for the music they were intended to communicate” (Evarts 1968). How prophetic! Some galleries show exhibitions of graphically notated musical scores. Back in 1986, the Serpentine Gallery exhibited musical scores by Stockhausen, Cage, Duchamp, and others in a show called Eye Candy: The Graphic Art of New Musical Notation. Music and art go hand in hand.

You might think it difficult to find a link to music and Geography, but a consideration of what Geography means in a Montessori classroom will make the link apparent. Under the umbrella of “Geography” we have, for one thing, the workings of the universe and the formation of the earth and our solar system. Pythagoras, the Greek philosopher and mathematician was interested in music. He suggested that each planet in the solar system, while spinning, emitted a unique musical note. Put together, these notes emanating from the planets make a musical scale (Marchak 1999).

Other musicians, like Gustav Holst, who composed the symphonic piece The Planets, were fascinated with our solar system. Here on earth, music existed long before human beings thought to organize it. Nicole Marchak, in her article The Grace of Music postulates that music probably evolved “from essential rhythms of the natural world”. She assumes that “homo sapiens had the ability to make noises through the larynx…for the simple pleasure of being in tune with the sounds of the natural world such s crackling twigs, rustling leaves, babbling brooks, roaring rivers, and animal cries” (Marchak 1999). All of this speaks to the physical universe being an inspiration for, and a catalyst for the invention of music.

When we think of Geography we think of science, and there is wonder and fascination in the science of music. In fact, from the time of Pythagoras, music and science have been intertwined. Music is made of sound waves emanating from a vibrating body, traveling through the air, and reaching our eardrums. Sound waves travel through air in the same way waves travel through water. Sound is like light in some ways, because both are waves that emanate from a definite source. But unlike light, sound can’t travel in a vacuum. Children find great pleasure in the study of the science of sound.

As interesting as it is to explore music’s link to other areas of our curriculum, thinking about homo sapiens brings me back to my other point about music and its link to Cosmic Education: music is a uniquely human achievement.

Sound is a natural phenomenon. Other animals perceive sound in their environments, but it takes our human brains to organize sound into music. To do this, human beings make use of their three unique gifts: the imagination, the hand, and love (Travis 2009). Thinking back to those early human beings, “at some point sound evolved into speech with the growth of the human brain and the formation of groups of humans” (Marchak 1999).

Probably concurrent with speech, human beings started making sounds with objects or on their bodies. Eventually, they began to use their imaginations to envision devices that might make different sounds. They envisioned things they could beat on, blow through, or pluck. With their hands, they built early musical instruments. We know this happened because, music has always been a part of “the heritage transmitted by all human groups all over the world” (Marchak 2009).

As music developed, human beings began to figure out ways to write it down. Composers from the Greeks, to the Medieval period, to modern times, notated and passed on their music for others to enjoy. They held organized sounds in their minds and used their hands to write them down.

Therein lies the love. Out of love for humanity, composers of wrote down their music so as to transmit it to all of us who came later. Thanks to their efforts, we can listen to their beautiful music and share in their feelings. What’s more, these composers invite us to participate in the music. For, music doesn’t exist until we create it either by conceptualizing it in our minds, or by recreating it.

Unlike a piece of art, which exists without our efforts, a piece of music must be performed and heard in order to have shape. Imagine if that were true with visual art. A painting like Picasso’s Guernica would not be a painting at all, but a set of instructions on how to paint it. What is a musical score but a blueprint, a set of instructions for how to create a piece of music?

Composers drew us these maps, gave us these gifts, out of that human love that extends beyond time and space. In a way, the organization of the sounds of the natural world, the harnessing of sounds and the building of musical instruments so humankind can make and combine all manner of different sounds represents another aspect of the supranatura—the structure that mankind has built over nature—that Mario Montessori talks about. Music fits in with Cosmic Education because it is another testament to humankind’s triumph over nature.

Having established that music is a vital component of Cosmic Education because of its link to all subjects and because it is a unique testament to the achievement of human beings, we see that it can’t be left out. If we’re really implementing Montessori’s plan of Cosmic Education, then music is mandatory. “The presentations that the elementary teacher must be prepared to give must encompass all subjects, since Dr. Montessori’s aspiration was to give the older child the universe. Children should be working in the areas of biology, geography, geometry, history, mathematics, language, art, and music” (Pottish-Lewis 2014).

Montessori teachers transmit Cosmic Education through presentations, lessons, and “by giving story after story after story after story” (Stephenson 2002). Stories about music, about composers, about famous compositions, and about musical instruments and ensembles, inspire the child and spur her toward Great Work. When we tell these stories, we can make connections to other areas of the curriculum. We can appeal to the elementary child’s characteristics and get him fired up to learn more. Through stories about music, along with the other stories we tell, the child can begin to wonder about his contribution to humanity and his place in the universe.

MUSIC IS FUN

Suppose someone were to write a rebuttal to this article, replacing the word “why” in the title with “don’t” and “imperative” in the subtitle with “detriment.” The article could be buttressed with studies that support the counter argument that music is a waste of time, that music causes chaos in children, that it’s superfluous, that it’s a distraction, and that it is in no way as important as the other more “academic” subjects. Even if this person could amass enough studies to shoot down the idea of music being beneficial, there is one thing that even the most pro-silence study could never deny: music is fun.

The smiles on the children’s faces when performing folk songs and singing games can’t be ignored by even the most cynical, most die-hard anti-arts educators. The children become absorbed in their collective excitement at making music together. They unite into one, 30-headed joyful being, moving, singing, playing instruments, and experiencing the same joy of music making that human beings for millennia have experienced.

The word music comes from either the Greek word musike, or the Latin musica, and it refers to the Muses, who, through their art, had the power to banish all grief and sorrow. Music is for communication of our spirits, of emotion beyond words. Mario Montessori wrote that “[music] mirrors the sentiments of men when joys and sorrows overflowed channels of expression offered by language” (Marchak 1999). He adds that music allows the [child] to “thrill” with other [children] and to be “transported by a flood of sound that fuse it with other [children] similarly uplifted” (Montessori 1956). Dr. Montessori herself initiated the inclusion of musical experience in her vision of the prepared environment (Marchak 1998).

After all, music, being important in daily living, good for brain development, helpful in improving emotional and body regulation and the mathematical mind, and, above all, fun, ought to be a vital component of the Montessori curriculum. If it’s good enough for the founder of our practice, it’s good enough for us.

WORKS CITED